In this conservative corner of California, a monstrous fire that killed four people and destroyed more than 100 buildings is being politically framed by many.

Some residents recognize the role of climate change in the increasingly devastating firestorms in California, but their real anger often centers on decades of government policy they believe has exacerbated the fire risk and made it harder to deal with the devastating McKinney fire in the Klamath National Forest.

Yreka, which is in the shadow of this national forest, was once a “wooden town” famous for its logging industry. Some residents here this week said the slow death of this industry coincided with an increased frequency of wildfires in the area as the vegetation became more and more overgrown.

“As a child, we rarely worried that fires would get out of control and destroy entire cities,” said Bill Robberson, a 60-year-old Siskiyou County resident and fourth generation Californian.

Experts say there are many factors behind a fire. Population growth has pushed more and more inhabitants to the junction of wilderness and cities, leaving more homes and people in danger. Moreover, man-made global warming contributed to a spike in temperature and searing dryness, creating a recipe for turning even the smallest spark into a firestorm.

Even so, some stakeholders in the community argue that the bureaucratic bureaucracy has prevented the necessary work from being done. Their concerns reflected the growing frustration of policymakers in Sacramento and Washington, who they said often do not care about the interests of rural, conservative Northern California.

“As a government, it seems we have no problem declaring a state of emergency on many issues, so why doesn’t Washington declare a public health and safety emergency based on forest health and climate change for the Pacific Northwest and make it a priority?” Asked Larry Alexander, executive director of the Northern California Resource Center, which sponsors the fire safety board in Yrece and other parts of the county. “It would be good for the forest, good for public health and safety, and it would also provide jobs for many people.”

Dissatisfaction with state and federal governments has been a common refrain among residents of the county that lies at the heart of the proposed state of Jefferson. The detached state would encompass parts of northern California and southern Oregon, where many residents of this largely remote and rural region believe they have been neglected by the governments of both states.

The Jefferson movement goes back decades – Yreka was the proposed capital in the original 1941 plan – but has gained new vigor in recent years as advocates of liberal democratic policies around issues such as gun control, immigration and taxation are against their interests. And as the region’s once thriving timber industry was increasingly constrained by regulation, ecology, technological advances, and other market forces, many residents looked towards the smoldering forests with a growing sense of betrayal.

“When we lost the logging industry in this area, it was catastrophic for us,” said Mayor Yreki Duane Kegg. “We have lost a large part of our economy, and the loss of a large part has an impact on many different problems – homelessness, people experiencing drug and alcohol problems. We’ve seen it over the years, and I attribute it all to the 1980s, losing our logging industry. ”

The log load is delivered to a sawmill in Weed, California.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

The schism has only worsened as the struggle between environmentalists, woodcutters and politicians heats up amid larger and more frequent fires. In 2018, then-President Trump accused the worsening fires in California of not raking the forest floor. In 2021, Governor Gavin Newsom condemned the US Forest Service’s “let it burn” policy after the 69,000-acre Tamarack fire spread to some communities near South Lake Tahoe, prompting the agency to reconsider its approach.

Alexander attributed much of the forest management backlog to environmental clean-up processes – such as those imposed by the Endangered Species Act to protect spotted owl habitats in forests – which he said could take two to five years. He also questioned whether top officials really understood the urgency of the situation.

“When it comes to prevention, we are so pitifully behind the curve of having enough fuel reduction and forest health measures,” he said. “It has to be 100 times what we do, just in terms of funding, resources and planning, and we just lag behind every year.”

Some work has been done locally, including a fuel reduction project on private properties bordering forests on the west end of Yreka. The work was financed by the Forest Service and was completed a few days before the McKinney fire broke out.

It was part of a $ 8 million project known as the Craggy Vegetation Management Project, which was developed by the Yreka Fire Safety Council, California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection and the Forest Service, and aims to improve fire resistance on approximately 11,000 acres. in the area, according to the project website.

However, as the Forest Service records show, it took more than seven years, and only just over a third of the 11,000 acres were processed. A spokeswoman for Kimberly DeVall stressed that while one section of the Craggy Project border stretched along Highway 96 where the McKinney fire was burning, the project was intended to “mainly improve fire defenses for the Yreka and Hawkinsville communities, which is about 10 to 15 miles to the southeast. from the place where the construction fires took place ”.

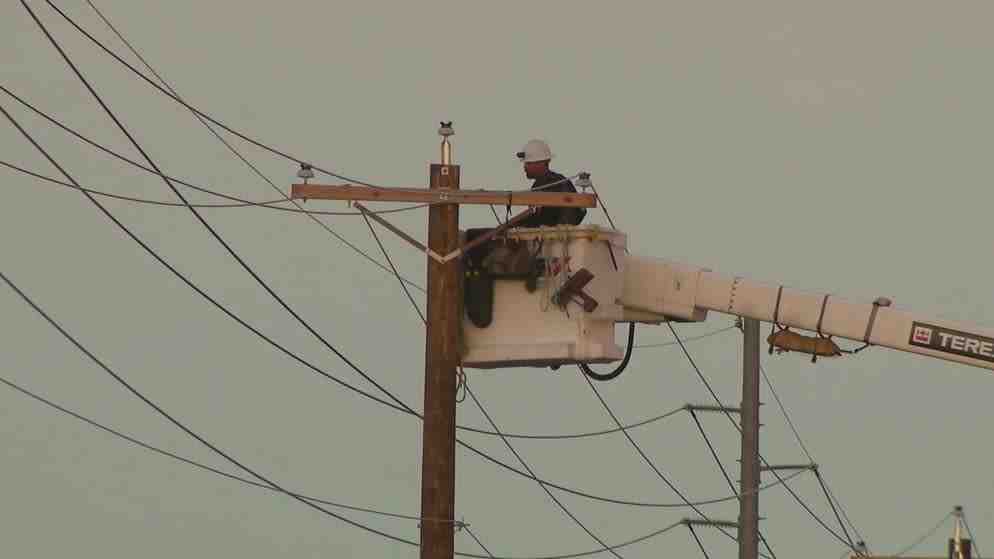

Firefighters stroll through the old town of Yreka, California on Tuesday as a McKinney fire charred the area.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Many residents affected by the fires in Northern California did not care which agency had jurisdiction over the vast swath of forests in the state, which included state, federal, and private lands. All that matters to them is whether the work is done.

“When we first moved here, it wasn’t like that,” said Nick Rouhier, a construction worker who has lived in Yreka since 2009. “We’ve had a fire season since around 2015.”

Earlier this week, Rouhier was using time off work – due to the evacuation and company closure – to remove some vegetation from his home’s yard, which was just outside the mandatory evacuation zone. He said he stayed close to home in case he had to “blow up” and leave quickly.

Rouhier attributed the regular appearance of wildfires in the area to a number of factors, including noticeably hotter summers and persistent droughts, but also said one topic among the locals was that “forests are not cared for.”

He wondered if there were enough resources to really manage a forest the size of Klamath, and noted that the side of the mountain overlooking his house hadn’t burned down in decades.

“I would be worried if I saw flames there,” he said.

He was echoed by MP Doug LaMalfa (R-Richvale), who has spoken openly about the state’s forest management practices in the past – even joining conservative governor candidate Larry Elder at a press conference in 2021, denouncing the way Newsom dealt with fires.

“I’m not shooting anyone who’s here,” LaMalfa said of the crews fighting the McKinney fire, “but at a higher level they fear lawsuits so much and are almost paralyzed.”

The neighborhood that LaMalfa represents has experienced several devastating fires in recent years, including the massive Dixie fire last year and the deadly camp fire in Paradise in 2018. He remembered when fires of 5,000 acres were considered large, while today they routinely exceed five and six figures.

“What has changed is 50 years of management change due to lawsuits, abuse of the Endangered Species Act and so on,” he said.

However, regional environmental groups said the Forest Service, not their lawsuits, slowed down some work in the area. The Klamath-Siskiyou Wildlands Center even offered “no objection” to the Craggy vegetation project, calling it “a welcome break from focusing on clearing down the backcountry after the fire.”

“We encouraged them to prioritize this project because it was located in existing dense wood plantations that can transmit fire very quickly,” said the organization’s director of security, George Sexton. He added that the use of traditional ecological knowledge, including the implementation of the prescribed fire, “was very effective and more is needed”.

“I think if we could all come to this with better intentions of ourselves, these things would be an opportunity to connect, not split, break up,” he said.

The paint is fading on the outside of an old sawmill in Siskiyou Mountain County in Weed.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

LaMalfa has criticized the Biden administration’s recently announced plans to tackle 20 million additional acres of federal forest in 10 years, noting that this is still only a fraction of what the agency oversees.

“It would take a hundred years to go through all of the nearly 200 [million acres],” he said. “We have to do five times or more and we have to be aggressive because we keep failing.”

Bruce Cain, political scientist and director of the Bill Lane Center for the American West, said Bruce Cain, political scientist and director of the Bill Lane Center for the American West, said Bruce Cain, political scientist and director of the Bill Lane Center for the American West, although they contributed to this failure in forest management – with an increase in population and lack of funds. Stanford.

Politicization makes people “less likely to think climate change is the cause, less likely to take steps to even protect themselves from smoke, wear masks, believe their property is under threat,” Cain said. “It has that effect. At stake is not whether people will eventually learn – but the rate at which they learn that we have to do something about it, and that may take a little longer because of the polarization. “

Cain recently co-authored a study which found that Republicans may be generally more opposed to spending public money on resilience measures than Democrats, but personal experience with fire diminishes that opposition. However, he also said that state and federal agencies are fighting to get the necessary maintenance done, and that land management is “something we’re not doing well in California.”

“It’s not something that is easy to sell because people want the right to live where they want to live and communities want the right to generate income the way they want to generate income,” he said. “And that’s where the fighting is most likely to happen.”

This friction was emphasized by the strong pro-logging current flowing through Yreka and described by Mayor Kegg.

“My family has been logging for many years, so we’ve seen a lot of things that unfortunately haven’t been going in the right direction for many years in terms of proper forest management, and that’s happening in many places here in true Northern California and Southern Oregon – said Kegg.

“We can still preserve our habitat for wildlife and continue to protect it for all, and we can carry out logging, which is a valuable resource for our community and on which it is largely built,” he added.

A similar sentiment is shared by Kim Greene, mayor of the nearby town of Weed, which suffered similar damage in the 2014 Boles fire.

“Our watchword at Weed is,” You can cut it down, you can graze it, or you can burn it, “she said. “The state of California decides to burn it.”

The Yreka store touts the proposed state of Jefferson, which would cover much of northern California and southern Oregon.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Research has shown that government fire suppression policies, along with the displacement of indigenous peoples who burned the cultures, contributed to denser vegetation in the Klamath bioregion. However, experts say that commercial logging could lead to the replacement of larger, fire-resistant trees with atypical densities and young trees that are more susceptible to the spread of fire.

“There is ample evidence that simply cutting and thinning can actually make the problem worse,” said Jeffrey Kane, professor of fire ecology and fuel management at Cal Poly Humboldt. “Because it’s not just about removing trees, it’s about reducing fuel, and in many cases when you thin the forest you don’t always remove fuel.”

Kane said logging “by itself cannot help prevent such fires,” but noted that it could be part of a multi-faceted solution to help tackle the problem of excess trees and increased fire activity due to climate change.

“It is possible. It will take work, it will take money, it will require working together and not getting bogged down in these divisive arguments,” he said. “Because when you row against each other, you won’t get very far.”

Given the death toll of the McKinney fire, which is likely to rise as authorities sift through the rubble of houses, it’s clear that the matter is as personal as it is political.

Robberson, a fourth-generation resident, said it was hard not to worry about the increased frequency of fires. He sat down at a table on the main street of the city, mostly empty, where guests were greeted with a faint smell of smoke and a banner saying, “Join State Jefferson.”

The season of wildfires has become such a regular and destructive part of life in Yreka that it contemplates something his Californian ancestors would never dream of: leaving the state altogether.

“The environmental impact, the economic impact – and the smoke – it’s hard to think about,” said Robberson. “And that doesn’t help with tourism. You don’t want to be known as a place that is on fire.