Over the past two years, COVID-19 has followed a predictable, albeit painful pattern: as coronavirus transmission rebounded, California was flooded with new cases, and hospitals overburdened with a flood of seriously ill patients, an alarming number of whom are dying.

But in a world flooded with vaccines and therapies, and healthcare providers armed with the knowledge gleaned from a pandemic, the latest wave is not following this scenario.

Despite the widespread spread of the coronavirus – the latest peak being the third highest of the pandemic – the impact on hospitals has been relatively small. Even with the increase in transmission, deaths related to COVID-19 remained fairly low and stable.

And it happened even as officials largely avoided the new restrictions and mandates.

In some respects, this is what should happen: as health experts keep getting better at identifying, vaccinating against, and treating the symptoms of the coronavirus, new spikes in cases should not lead to spikes in serious diseases.

But today’s environment is not necessarily tomorrow’s benchmark. The coronavirus can mutate rapidly, potentially changing the public health landscape and deserving a different response.

“The only thing that is predictable with COVID, in my opinion, is that it is unpredictable,” said UCLA epidemiologist Dr. Robert Kim-Farley.

While it’s too early to say for sure, there are signs that the current tide is starting to recede. According to data compiled by The Times, during the week ending Thursday, California reported an average of just over 13,400 new cases per day – compared to the most recent high of almost 16,700 per day.

By comparison, last summer’s Delta growth averaged nearly 14,400 new cases per day.

More than 8,300 coronavirus patients were hospitalized on certain days at the top of the Delta – almost three times more than during the last wave.

The difference in the impact of each stroke on ICUs was even greater. During the Delta, there were days when more than 2,000 coronavirus infected patients were in intensive care units across the state. However, in the latest wave, this daily census has reached around 300 so far.

This hospitalization gap shows how the pandemic has changed.

“At the very beginning of the pandemic, we immediately saw that they were changing the game of the vaccine, easy access to testing and treatment – and now we have it all,” said Barbara Ferrer, director of public health for Los Angeles County.

“He doesn’t say the pandemic is over. This is not what we achieved, ”she emphasized. “What we have achieved is risk reduction, but we have not eliminated it.”

And while the number of hospitalizations was lower, during the last wave overall, Ferrer noted that each infection still carries its own dangers – not only severe illness, but also the risk of long-term COVID. She said taking individual steps to protect yourself has the added benefit of helping to protect those around you, including those who are more likely to develop serious symptoms or work in places where they regularly come into contact with many people. .

“It is clear to me that layering in some protection is still the way to go while enjoying almost anything you want to enjoy,” she said.

California’s most restrictive efforts to contain the coronavirus ended almost exactly a year ago, when the state celebrated its economic reopening, lifting virtually all the restrictions that had long underpinned its pandemic response.

About a month later, as the then novel Delta variant was rampaging, some parts of the state restored mask seats in hopes of blunting the transmission.

At the end of the year, another new enemy would appear: the Omicron variant. This highly contagious strain caused an unprecedented spread of the virus, causing a surge in cases and hospitalizations, prompting officials to reissue a mandate to mask public premises.

The fury with which these two tides struck made some fear and others advocate the return of stringent orders that restricted people’s movements and shut down wide swaths of the economy. However, both waves came and went without Californian officials resorting to that option.

And during that final wave – fueled by the alphanumeric soup of Omicron sub-variants including BA.2 and BA.2.12.1 – such aggressive behavior seems unthinkable.

“I think deep in my heart, if we don’t see a new variant that escapes our current vaccine protection, we won’t have to go back to the more drastic tools we had to use at the start of the pandemic, when we didn’t have a vaccine, when we didn’t have access to testing. when we didn’t have therapeutic measures, ”Ferrer said in an interview.

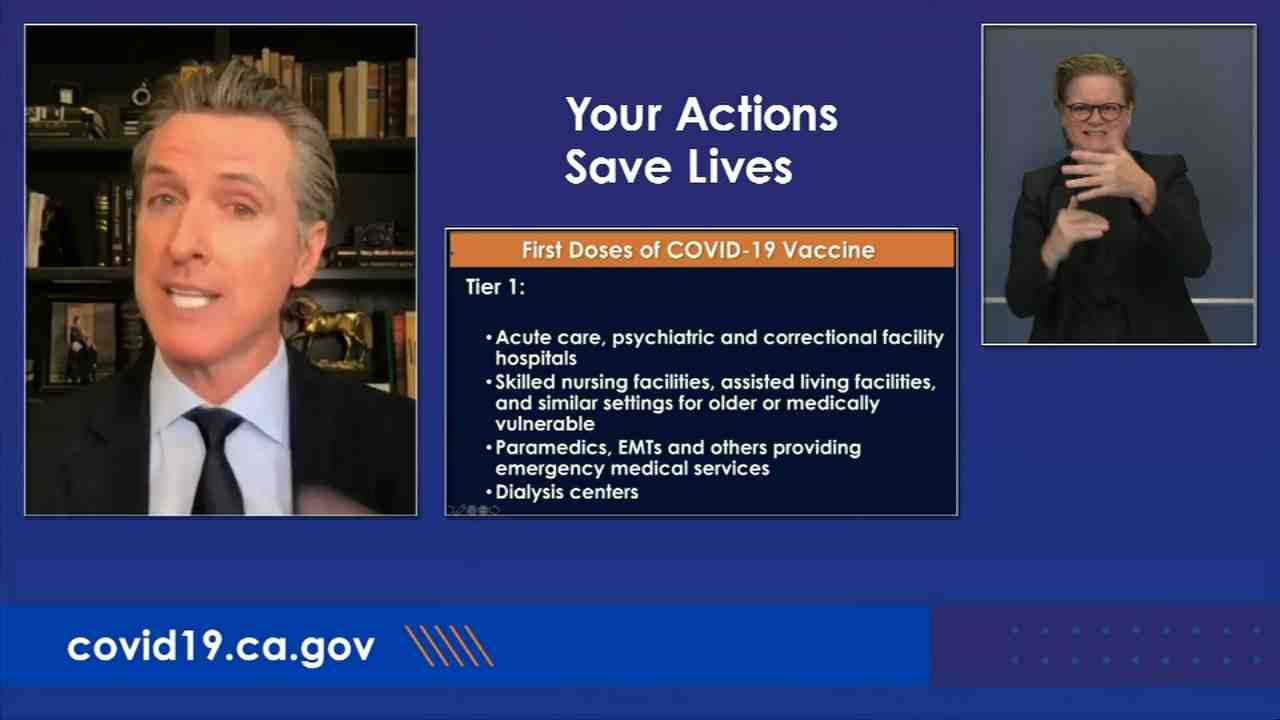

During both Delta and Omicron’s initial growth, California “carefully assessed the unique characteristics of each variant to determine how best to deal with changes in virus behavior, and used lessons from the past two years to approach mitigation and adaptation measures through effective and timely strategies ”, according to the Department of Public Health.

“These lessons and experiences have influenced our approach to managing each growth and variant. In addition, more disease control tools were available with each successive shock, including Delta and Omicron discharges, ”the department wrote in response to a query from The Times. “So, instead of using the same mitigation strategies as before, CDPH has focused on vaccines, masks, testing, quarantine, improved ventilation, and new therapies.”

Stan has also abandoned its previous practice of setting specific thresholds to tighten or loosen constraints in favor of what it calls the “SMARTER” plan, which focuses on preparing and applying lessons learned to better base California on future increases or new variants.

“Each growth and each variant has unique characteristics that are unique to the specific conditions of our neighborhoods and communities,” the Department of Public Health said in a statement to The Times.

The chief one, the department added, is vaccinated and fortified when qualified and properly wears high-quality face masks when warranted.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends public indoor masking in counties with a high COVID-19 community, the worst on the agency’s three-tier scale. This category not only indicates significant community transmission, but also that hospital systems may be burdened by coronavirus infected patients.

“We are definitely not at the level where you would say,” Okay, now it is, and I quote, endemic, and we’re just going into business as usual, “said Kim-Farley. “But I think it probably indicates what we can see in the future, that we will see a low level in the community, people can relax and lose their vigilance a bit. But then there will be other times when we will be able to see the waves coming. … This is the time when we are masking again. So I think it can turn on and off a bit, and hopefully these waves will get thinner, more distributed and less intense as it progresses. “

On Thursday, 19 California counties were at a high community level – Alameda, Butte, Contra Costa, Del Norte, El Dorado, Fresno, Kings, Lake, Madeira, Marin, Monterey, Napa, Placer, Sacramento, San Benito, Santa Clara, Solano , Sonoma and Yolo. However, only Alameda County reintroduced the public mandate to use internal masks.

Ferrer said Los Angeles County would do the same if it were in a high-level COVID-19 community for two consecutive weeks.

LA County, like the state as a whole, continues to strongly recommend residents wearing masks in public. But Ferrer admitted that it was “a very difficult needle to thread,” and said that an unintended consequence of many years of health dictates could be that people do not understand the urgency of the recommendation.

“People are now assuming that if we don’t issue orders and require security measures, it’s because it’s not necessary, and that’s not what we meant,” she said. “We’ve always benefited from having people who can listen, ask questions and then, for the most part, conform to security measures. And I think because so long has passed, because at this point there is so much fatigue and desperation to go back to the usual practices, people are waiting for this order before taking any reasonable precautions.

What are the symptoms of the COVID-19?

Symptoms may appear 2 to 14 days after exposure to the virus. Common symptoms may include: fever or chills; cough; dyspnoea; tiredness; muscle or body aches; headache; new loss of taste or smell; sore throat; hyperemia or runny nose; nausea or vomiting; diarrhea.

Can i have COVID-19 if i have a fever? If you have a fever, cough, or other symptoms, you may have COVID-19.

How long does it take for COVID-19 symptoms to start showing?

People with COVID-19 have reported a wide range of symptoms, ranging from mild symptoms to severe illness. Symptoms may appear 2-14 days after exposure to the virus. If you have a fever, cough, or other symptoms, you may have COVID-19.

How long does the virus that causes COVID-19 last on surfaces?

Recent studies have assessed the survival of the COVID-19 virus on a variety of surfaces and found that the virus can remain viable for up to 72 hours on plastic and stainless steel, up to four hours on copper and up to 24 hours on cardboard.

Can COVID-19 be transmitted through food?

There is currently no evidence that people can catch COVID-19 from food. The virus that causes COVID-19 can be killed at temperatures similar to other known viruses and bacteria found in food.

What do I do if I have mild symptoms of COVID-19?

If you have milder symptoms, such as fever, shortness of breath, or cough: stay home unless you need medical attention. If you must come in, please call your doctor or hospital first for directions. Inform your doctor about your illness.

When do symptoms of the coronavirus disease typically start?

People with COVID-19 have reported a wide range of symptoms, ranging from mild symptoms to severe illness. Symptoms may appear 2-14 days after exposure to the virus.

What medication should I take for mild COVID-19 symptoms?

If you are concerned about your symptoms, the Coronavirus Self Check Tool can help you make the decision to seek care. You can treat your symptoms with over-the-counter medications like acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil) to help you feel better. Find out more about what to do if you are sick.

What are some of the first symptoms of COVID-19?

Early symptoms reported by some people include tiredness, headache, sore throat, or fever. Others experience a loss of smell or taste. COVID-19 can cause symptoms that are mild at first but then become more severe over the course of five to seven days, with an increase in coughing and shortness of breath.

When do symptoms of the coronavirus disease typically start?

People with COVID-19 have reported a wide range of symptoms, ranging from mild symptoms to severe illness. Symptoms may appear 2-14 days after exposure to the virus.

What are some of the most common symptoms of COVID-19?

• Fever • Cough • Fatigue Early symptoms of COVID-19 may include loss of taste or smell.

What is the treatment for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults (MIS-A) from COVID-19 in adults?

For now, the literature has suggested steroids, IVIG, and adjunctive therapy for MIS-A (Ahmad, May 2021; Davogustto, May 2021). Based on current knowledge, the CDC recommends vaccination with COVID-19 as the best protection against MIS-A.

What is the pill Paxlovid used for in COVID-19?

Paxlovid is an oral antiviral pill that can be taken at home to help high-risk patients get sick enough to require hospitalization. So, if you test positive for coronavirus and your doctor gives you a prescription, you can take the pills at home and reduce your risk of going to hospital.

Does Paxlovid give you a bad taste in your mouth?

If you notice a bad taste in your mouth after taking the Paxlovid COVID-19 antiviral tablet, you are not imagining it. “About 5.6% of the people who took Paxlovid in the study reported a taste disorder, that is, a change in the taste in their mouth,” says Dr. Shivanjali Shankaran, RUSH’s infectious disease specialist.